A Wind Rises from the East

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) is alive and well in the Lacandon Jungle.

Health to you, Mexican brothers and sisters!

Health to you, campesinos of this homeland!

Health to you, the indigenous of all the lands!

Health to you, Zapatista fighters!

Zapata, in being arrives!

In death he lives!

Viva Zapata!

Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, April 10, 1994

It happened quite suddenly. The Tiger of the South rose and fell back down within the course of a decade marked by bloodshed and civil war. When he did fall in 1919, the people took it upon themselves to carry his bullet-riddled corpse through the streets for twenty-four hours. He came from the people, and to the people he was returned; this time as a martyr. Upon hearing the news of Zapata’s death, an inhabitant of Tepoztlán is quoted as saying, “It hurt me as much as if my own father had died.”

And yet, it takes much more than bullets to kill a God. Emiliano Zapata was a mere mortal, but his spirit had been present among the people for nearly five-hundred years, dwelling in the long derelict shadow of a despotic, colonialist ruling. From the ashes of a failed uprising, new voices emerged. They started as whispers, murmurs of rebellion and the New Order that would soon emerge.

Chief among these voices was a fiery, spirited college student from the northern reaches of the Mexican empire. Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente (later decorated as Subcomandante Marcos, and now Subcomandante Galeano) rose to prominence as an outsider, one who possessed the ability to strike sparks across a nation during a period of all-time ignitability. His sole focus quickly became the southern state of Chiapas, the place where it all began. He wrote,

[The indigenous peoples of Chiapas] were born dignified and rebellious, brothers and sisters to the rest of Mexico’s exploited people. They are not just the product of the Annexation Act of 1824, but of a long chain of ignominious acts and rebellions. From the time when cassocks and armor conquered this land, dignity and defiance have lived and spread under these rains.

In its current form under the leadership of Subcomandante Galeano, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) has nominally existed since 1983. Since then, they have continued to wage war against the Mexican state, although an uneasy ceasefire has been maintained since 2014. Their goals and ambitions are still the same, asserting that, “the fee that capitalism imposes on the southeastern part of this country makes Chiapas ooze blood and mud.” Neoliberalism, globalism, and international trade have inflicted more harm on these people than any state-sponsored militia, bomb, or curable disease (which continued to kill thousands of indigenous peoples in Mexico up through the 1990s). Subcamandante Galeano sums up the organization’s goals best, in a speech delivered on March 1, 1994, addressing the Mexican people and the governments of the world,

In our dreams we have seen another world, an honest world, a world decidedly more fair than the one in which we now live. We saw that in this world there was no need for armies; peace, justice and liberty were so common that no one talked about them as far-off concepts, but as things such as bread, birds, air, water, like book and voice.

Now we follow our path toward our true heart to ask it what we must do. We will return to our mountains to speak in our own tongue and in our own time.

Flash forward to another time, another place. Dawn creeps up slowly on the frost-covered iron-rail fences of a private gated community in Greenwich, Connecticut. It is nautical dawn, an hour before sunrise, and my traveling companion and I are waiting for the driver who will be delivering us to John F. Kennedy International Airport for our non-stop flight to Guadalajara.

No other municipality in America has done a better job at putting the fruits of capitalism on full display for all to see. Decadence, sometimes bordering on extravagance, paints the stucco exterior of every three-million-dollar, six-bedroom manor of every corporate executive, hedge fund manager, and venture capitalist who chooses to live within striking distance of downtown Manhattan. The shiny black Chevrolet Suburban that pulls up with a black-tie chauffeur attests to the purchase power of a globalized elite.

We had no intention of coming to Chiapas for rebellion during our spring break as sophomore college students. We were coming for birds. Our host in Chiapas, a 22-year-old, half-Spanish, half-Swedish graduate student based in San Cristóbal de las Casas, had carefully calculated the exact route and itinerary we would be following to ensure us the most species in just seven days of non-stop birdwatching. This may sound like a trivial goal, but to us, the birders from New England who had only ever entertained far-fetched dreams of exploring the Neotropics and its underrated potential for biodiversity and ecotourism, we felt like modern-day conquistadors setting out to explore a strange and fantastic landscape.

What we failed to realize was that our host, in an effort to ensure that we would be able to observe the maximum number of species possible, had charted us on a route that would take us directly through the Zapatista-controlled Autonomous Zone, with two nights scheduled in one of the most remote regions of the Lacandon Jungle. Traditionally, this is the area where the Mayan Gods are believed to dwell in an earthly paradise. Today, it is among the most exponentially developing areas in southeastern Mexico, with every day bringing with it new encroachment into the virgin lowland rainforest that remain as biogeographical ribbons around the dark green eye of the vast Reserva de la Biósfera Montes Azules.

I recall jokingly describing my trepidation of encountering a jaguar in the jungle to a noted ornithologist, a member of the “old guard” of field biologists, who had traveled widely throughout Mexico in the ‘90s. His response was serious, exact: “It’s not the jaguars you should be worried about eating you whole, it’s the Indians!”

Subcomandante Galeano best describes that moment of realization, when you inevitably come to terms with being in a country that is not your own,

Imagine a person who comes from an urban culture. One of the world's biggest cities, with a university education, accustomed to city life. It's like landing on another planet. The language, the surroundings are new. You're seen as an alien from outer space. Everything tells you: “Leave. This is a mistake. You don't belong in this place”; and it's said in a foreign tongue. But they let you know, the people, the way they act; the weather, the way it rains; the sunshine; the earth, the way it turns to mud; the diseases; the insects; homesickness. You're being told. “You don't belong here.”

Upon our arrival in San Cristóbal de las Casas from Guadalajara, it became evident just how stratified our surroundings were. San Cristóbal, a city of less than 200,000 situated at 7,200 feet above sea level (far above the lowland jungles—it is instead a tropical pine-oak environment), is a melting pot of expatriates and tourists from all over the world. You can hear English and French being spoken readily in the narrow one-way streets and hole-in-the-wall cafés; a vista stolen right from any other European urban setting. There are buskers who play the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Sublime in a Spanglish creole, and retired businessmen from Mexico City who go about smoking Cuban-imported cigars and peering out from beneath Panama-style fedoras. A group of sweaty German tourists dab at their white foreheads while guffawing over a piece of anarchist graffiti etched onto the side of colectivos station.

A few blocks away from the picturesque Church of Santo Domingo, where the 1994 Zapatista uprisings came to a head, one finds evidence of a wholly different San Cristóbal. Here, jungle refugees who speak both Tzotzil and Spanish, having been displaced from their ancestral homelands, push you to buy beads and hand-crafted textiles for as little as twenty pesos. The streets are awash with mestizos who have just barely been able to cling onto their cultural integrity with the tiniest ounce of pride and sober humility in their deep-rooted heritage.

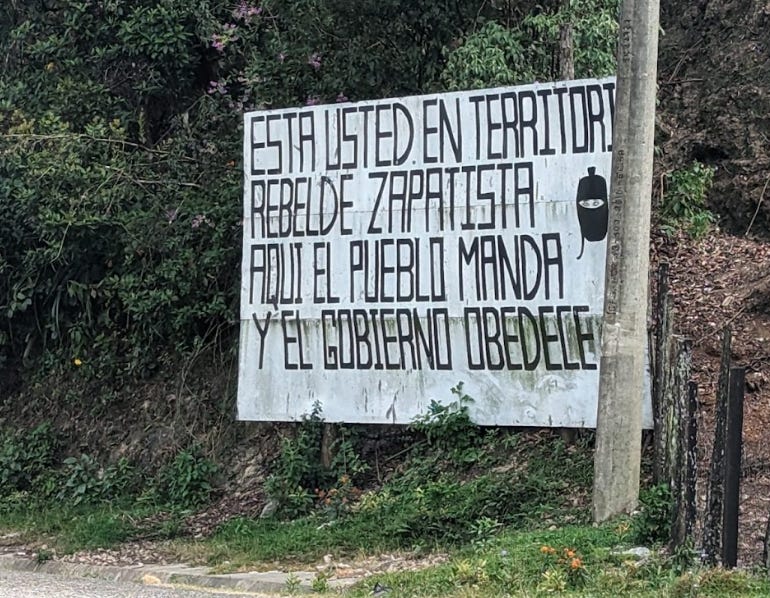

One drives down the mountain a little ways, and within thirty minutes, after passing through Teopisca, you have entered the Zapatista-controlled Autonomous Zone. You are immediately greeted by a glaring white sign that says, “Está usted en Territorio Rebelde Zapatista, aquí el pueblo manda y el gobierno obedece” (You are in Zapatista Rebel Territory, where the people rule and the government obeys). There are other signs too, some of them in Tzotzil, others in the native Tzeltal. Chances are, if you switch on the radio in your car, you might tune into a station that is dictated solely in one of the two dialects. Only a few Spanish words are supplemented in to describe dates, times, and months of the year.

The locals are extremely suspicious of white foreigners here. We stop at a roadside convenience store, and the old man behind the counter grills us about our government affiliations and business in the countryside. I want to buy an energy drink after my long international voyage, asking that David, our host, translate for me. He debates with the man for a solid minute-and-a-half, eventually turning to me, totally pallid, and exclaiming plainly, “He will not serve you.”

I learned much later on that the Zapatista communities have emphasized an approach towards an autonomous, self-sustaining organization that appeals towards “the wind from below” (a social tactic) rather than “the wind from above” (a political tactic). Subcomandante Galeano makes the distinction thusly,

... a revolutionary proposes fundamentally to transform things from above, not from below, the opposite to a social rebel. The revolutionary appears: We are going to form a movement, I will take power and from above will transform things. But not so the social rebel. The social rebel organizes the masses and from below, transforming things without the question of the seizure of power having to be raised.

These established forms of robust mutual aid have supplanted any need for extralimital commerce with the outside world, which explains why the shop owner abruptly turned me away. In this sense, the Zapatistas operate according to the early 20th-century German anarchist Gustav Landaur’s definition of the state as “a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a mode of human behavior; we destroy it [by] behaving differently.” It is something that can and should be opted in or out of voluntarily. There is no great triumphant or glorious revolution on the EZLN agenda—something that was fixated on to the point of obsession by innumerable Marxist and Leninist zealots. The British anarchist Colin Ward expands on these ideas in his essay “The Unwritten Handbook” from the perspective of his native England,

The vacuum created by the organizational requirements of a society in a period of rapid population growth and industrialisation at a time when unrestricted exploitation had to yield to a growing extent to the demands of the exploited, has been filled by the State, because of the weakness, inadequacy or incompleteness of libertarian alternatives. Thus the State, in its role as a form of social organization rather than in its basic function as an instrument of internal and external compulsion, is not so much the villain of the piece as the result of the inadequacy of the other answers to social needs.

The Zapatista movement has since sought to remedy these inadequacies through self-help, mutual aid, and spontaneous, free-forming organization. Ensuring that the movement remains autonomous and free from conventional capitalist restraints has always been a key component of the EZLN manifesto. It is what has allowed them to persist up through today. However, the means necessary to defend this way of life have not come without their price…

“Wake up. I need you to watch the car,” says David as I emerge from the restless slumber I have maintained from driving over three hours across the state of Chiapas, despite countless miles of mind-rattling topes.

I awake to find chaos, confusion, and disorder all around me and in every direction. Cars are lined up along the side of the road stretching back for as far as the eye can see, and several stern-looking men in collared shirts are walking around in the late twilight hours of the day with sour expressions. We are somewhere along the narrow two-lane expressway that runs from Comitán to San Cristóbal.

“I am going to try and figure out why we’re being stopped. Just stay here,” he says, nodding to the two other passengers in the vehicle with me.

Immediately my senses go on high alert. I have heard of road blockades before, but usually, they are accompanied by highway robbery. This is not the case, since quite literally every other car on the road has been stopped by the same occurrence. Some people are beginning to turn around and start the long drive back to Comitán, just as the sun slips down beneath the western ridgeline. A Lesser Roadrunner skips across the road in front of us, seemingly without fear of traffic.

David returns nearly ten minutes later with a familiar sour look on his face. He was not able to get a straight answer from any of the other stopped motorists, so he proceeded to make his way to the front of the line of cars. There, he encountered the root of our present predicament. He shows us a picture he took with his phone of an 18-wheeler big rig lying perpendicular against the road so that both directions are blocked to oncoming traffic. A white banner stretches out across the trailer, with EZLN insignias printed on it in black and red.

We never made it to San Cristóbal that night. Instead, we backtracked to the nearest hotel in silence.

I often joke about being an opportunistic photographer. I pull out my camera with baited breath every time I have a subject in front of me that I think is meaningful enough to be captured. The timing has to be perfect, and if I falter with my execution, then the moment is ruined and the breath is wasted. Other times, mainly through dumb luck, I can get people to experience that moment with me, even if it is just through a single click of the shutter. My obligations towards journalism are not that much different, which is why I see no time like the present to make my point wholly clear.

Despite their lack of media attention in recent years, the EZLN is alive and well in Chiapas, a region that holds close to 15 percent of Mexico’s total indigenous population and the highest illiteracy rate in adults. Native peoples across southeastern Mexico still lack access to reliable energy sources following the rejection of a major energy reform by the Mexican Supreme Court last year. The state-owned Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) still refuses to invest in alternative sources of energy, resulting in widespread blackouts across Chiapas. In February of 2019, a nonviolent EZLN protester named Teófilo Garcia Sarabia was unfairly tried and sentenced in Oaxaca following a ten-day power outage linked to CFE. Later this year, the 1550-kilometer-long Trans-Isthmic Corridor will be completed, traveling directly through indigenous-occupied territories.

The presence of foreign nationals in Chiapas has not improved the humanitarian crisis by any means, even with the best-intentioned tourists and snowbird hippies who flock to San Cristóbal during the dry season. Paul Theroux, one of the foremost travel writers of the last century, has largely criticized these toothless, naïve attitudes in response to State-inflicted oppression, scoffing at the hypocrisy that the “liberal’s paradise seems to be a place where he can hold leftist opinions in a lovely climate.” The result is a political complicity that cultivates the colonialist attitude of a “strong white man who has what he wants at the expense of millions of people who serve him in one way or another; he has everything, those around him have nothing.” He becomes Tarzan of the Jungle, who, whether subconsciously or not, believes that,

It is wrong—because it is unnatural—to try and settle jungle quarrels. It proves nothing. The animals may chatter and squabble, but this is of no concern to Tarzan; this is nature at her purest and should not be interfered with.

Until that time when the Tiger of the South rises again and the State of Mexico will take full accountability by signing its name in sanguine ink under the list of freedom fighters it has unjustly slaughtered, I can not support those who blindly go about abetting these injustices with the purchase power of their American dollar by traveling there without these considerations.

This essay is my humble attempt at repentance.