In the summer of 2020, I observed a group of squatters resurrect a decaying sea mansion on a small, lawless island off the coast of Massachusetts. Last year, I attempted to track down these squatters on their own turf, by driving a distance of 3000 miles round-trip into the depths of the Florida Keys. I never set foot on their fabled anarchist island, but my fascination and deep admiration of the Wisterians has persisted nonetheless. The term “Shadow Country” is borrowed from Peter Matthieson’s novel of the same name.

There is the Sunshine State, that is, the tropical peninsula we associate with Disney cruise ships and snowbirds flocking at Miami Beach. Then there is Shadow Country.

The latter, although it may fit into the same geographic perimeters of the former, exists on a wholly different plane of existence: one situated just below the salt-caked palm leaves and neon blue horizons characteristic of the Sunshine State. I have come to know a few denizens of both worlds, and although they are estranged from each other—largely on the basis of household income and educational background—the inhabitants of these respective planes have a single, fundamental thread that unites them: they all fall victim to the wayward belief that Florida is home to the fountain of youth.

Indeed, this was the idea popularized as far back as the 16th century, when the conquistador Ponce de León strode gallantly into the heart of the Florida Everglades, and from his cup would draw any moving body of water in a land dotted with stagnant, alkaline puddles. The mission was ultimately a failure, and with the calculations of the Spaniards foiled, the mythos surrounding the fountain of youth was lost to four hundred years of bloodshed resulting from colonialist expansion in the New World.

Or, so the legend goes.

But de León also never spent a night in Miami during the height of spring break hedonism, or joined a busload of retirees at the shooting range on a Saturday morning. If de León were alive to see any of this today, he might well be convinced, at least for a moment, that somebody had whacked the faucet clean off his fabled fountain.

It happened quite spontaneously, sometime between the rise and fall of the American Social Security Program. A whole generation had become reinvigorated. The rumor of a fountain existing somewhere south by southeast of the Florida panhandle had galvanized an aging nation, at a time when thirst was at an all-time high. The young people were after it too, and they came in droves. In fact, the young people had been convinced by the older generation that the waters of the fountain flowed freely out from Lake Okeechobee, infiltrating everything downstream from Homestead to Marco Island.

There is a reason that Florida continues to dry up today despite rising sea levels. The reason is that too many people have bought into the belief that this water has come direct from the fountain itself, when in reality, they are still reaching for the same shallow pools that de León and his men had sipped so many years ago.

The dichotomy that exists between Sunshine State and Shadow Country is perhaps most evident from Key West, the synaptic terminal of a long chain of islands forming the Florida Keys. The 113-mile Overseas Highway ends here, and the few sandy islands and coral atolls that exist beyond this point of departure lie perpetually out of reach for the land-chained visitor from afar. And yet, even without an outboard motor or sea kayak, if you walk to the end of Duval Street and look West, a whole world emerges on the horizon, just beyond the Disney cruise ships and world-class luxury spa retreats.

Two islands, both entirely alike in both size and diameter. One is the result of a single man’s desire to terraform and commercialize a Cold War-era fuel tank depot. Privately owned among its residents, Sunset Key is only accessible via water taxi, and residents here drive golf carts instead of big, cumbersome SUVs. Land speculation runs awry. Clocking in at just 27 acres, the few remaining lots of buildable land are sold off in parcels to the tune of $1.5 million. Long, languid afternoons spent on the docks sipping mimosas, children in starch white polos and tennis shoes riding bikes without helmets, and a young woman traversing the shore by moonlight, barefoot and clad in linens—this is the vision of the Sunshine State. The triumph of the developer, and in this case, the profiteer.

Just a stone’s throw away from Sunset Key lies Wisteria Island. In 2011, the island was determined to have been owned by the Bureau of Land Management, after much debate stemming from the island’s most unusual inception as a byproduct of military dredging in the early 1900s. Myths abound in Key West surrounding the inhabitants of Wisteria. Thought of by natives to be a safe haven for society’s extralimital, the island is rumored to host liberals, anarchists, squatters, and madmen alike. A bartender in The Meadows district warns me against the island’s supposed corruption of local youth, having seen a teenager, “probably not older than sixteen,” being led into the forest there by two bare-chested women.

Very few people on Key West do not have stories about Wisteria, and even fewer have never heard the name to begin with—but these, I must conclude, are most likely tourists. They have only ever experienced the Sunshine State, never having stepped foot in Shadow Country.

I first learned about Wisteria Island in 2020. I was living on another island at the time, one that is entirely incomparable to either Sunset Key or Wisteria, although it shares elements of both.

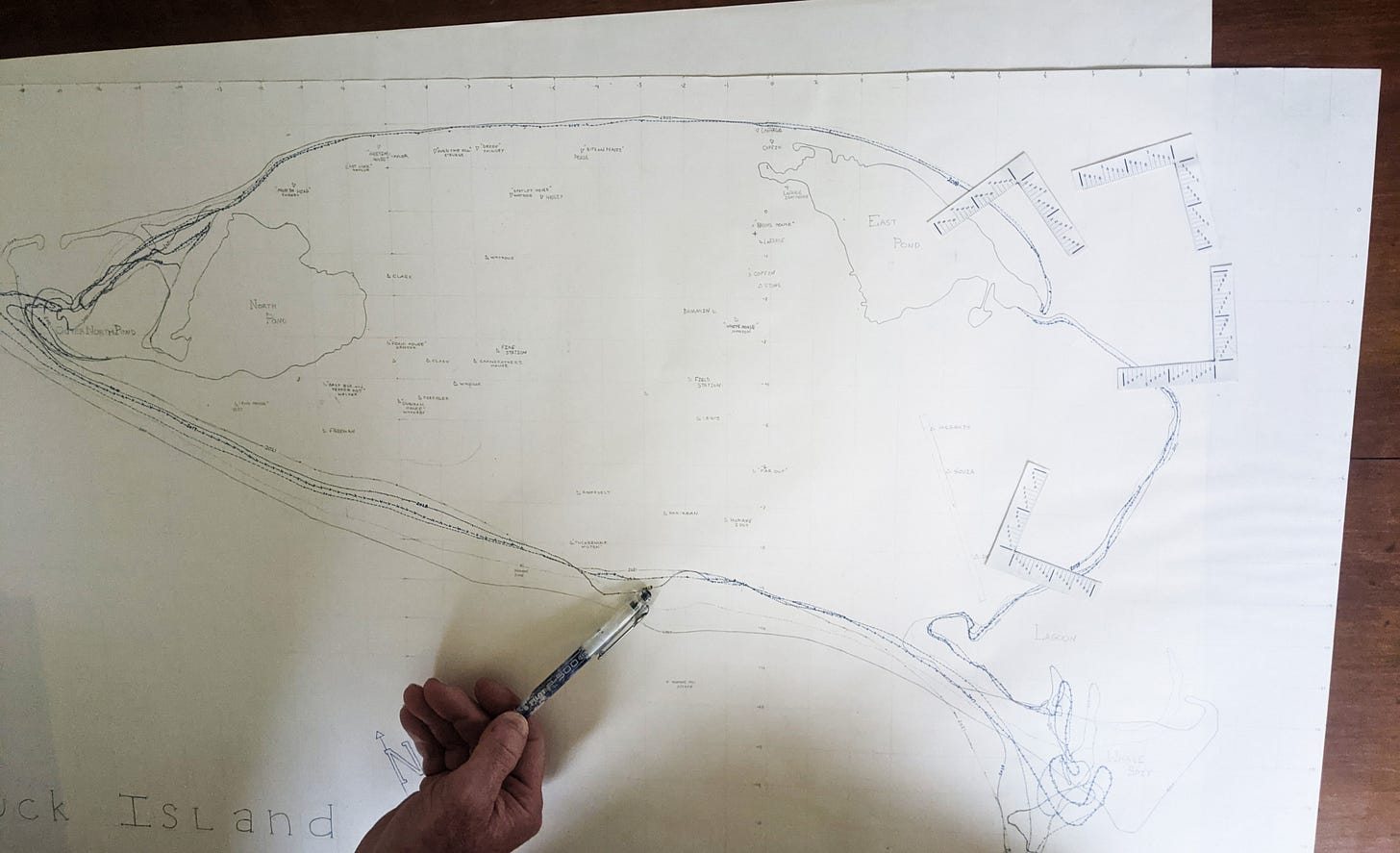

Tuckernuck Island is a small, privately-owned island off the coast of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. A mere thirty-eight residences exist on an island just shy of 900 acres (c.f. Sunset Key with 48 single-family homes squeezed onto a mere 27 acres). There is no electrical grid, no paved roads, no year-round infrastructure, and zero commercial zoning. A few cars are distributed unevenly across the island, including a repurposed military HMMWV—a relic of the Gulf War—now functioning as the island's only fire truck. The families who live here today share the same names as those who built these sea mansions in the nineteenth century. Dammin. Stone. Coffin. In the winter, it becomes a ghost town. The year-round population of Tuckernuck is a tentative and questionable "1".

The law does not apply to Tuckernuck. It is so remote, so isolated, so completely forgotten that not even the coast guard makes it out to this lonely island.

During my summer on Tuckernuck, I was introduced to inhabitants of Wisteria who wielded titles like “squatter” and “anarchist” with pride, but also those who were more reserved about their radical tendencies.

They were a young crop, most in their mid-to-late twenties. Some were true outcasts (their pasts either obscured or crossed out), others were recovering drug addicts. Some held degrees in lucrative fields such as Biology and Physics.

They had all sailed north from the Keys to reach the mild climate of the Nantucket archipelago, presumably to escape the oppressive heat of the Florida Keys, attracted by the allure of an island devoid of influence from the State. They were sea nomads, using Wisteria as their port of call.

Tuckernuck had the ability to bring together many people from a swath of different social and cultural backgrounds, depositing them on a tiny island that offered very few resources, uniting them under an overwhelming sense of remote loneliness, set against the backdrop of an austere New England coastal retreat, lost in time and lost in memory.

The Wisterians who inhabited Tuckernuck during the summer of 2020 were living in this old decaying saltbox estate raised in the late 1800s. When I arrived on the island for the first time in April of that year, this house lacked running water and electricity, and the shingles on the roof were in desperate need of repair. Barn Owls entered and exited the house at will through a broken window panel on the second floor. The Stone House was stuck in the Gilded Age, and it would take more than a village to drag it into the present.

The Wisterians arrived a few weeks later, and murmurs soon began spreading across the small island community. They brought mopeds, and the mopeds were quick to be deemed “too noisy.” They brought dogs, and not long after the dogs started attacking the livestock. Guns were drawn at one point. Neighbors, although few and far between, clung onto the fraught sense of land autonomy they possessed to begin with, which they both concealed and coveted.

But the Wisterians also brought music. Sweet, sweet music. Every night, their singing and dancing would echo across the island. The trees on Tuckernuck are stunted and spindly; there is nothing to break the sounds bouncing across the heathlands. Sometimes, fantastic smells would writher in from the East, and you knew the Wisterians were having a clambake. They probably were better than you with a rake, anyways.

Surfcasting with them was like shooting into a bucket. Some of the biggest bluefish I’ve ever seen were caught in the presence of the Wisterians. They lacked the arsenal of jigs, poppers, missiles, and hellfires the Long Island surfcasters possessed, but they didn’t need those things. Their knowledge of the shoals was unparalleled, and they could make do with a few hand-coiled wire leaders and some spoons.

They even lacked a proper sea-faring vessel, something basically essential for travel to-and-from the island, in lieu of public water transportation. There was this dilapidated catamaran schooner that they had managed to bring up from the Keys, and they kept it on a mooring in nearby Nantucket. How they were able to procure a mooring in Nantucket Harbor, when today there is still a fifteen-year waitlist to even look at one, I will never know.

They made the commute between Nantucket and Tuckernuck on this fixer-up little lake boat, propelled along by a sputtering four-stroke outboard motor. This proved to work for their needs, as they did not need or want to return to the bigger island terribly often, except to buy cigarettes, groceries, and other supplies for the house. At some point during the summer, one of the Wisterians thought it would be a good idea to bring a baby grand piano back over from Nantucket. They did this by commandeering a 21’ Carolina Skiff, which was miraculously able to transport the piano across Madaket Harbor without incident. The locals on Tuckernuck were baffled. There had never been a piano on the island before.

Many people from across the island came over to the Stone House to hear the piano that day. The songs ranged from simple Heart and Soul duets to advanced free-form styles of jazz. And on that cold night in late June, with the fog still hanging low, the fire in the wood stove burned long into the night.

People took a different attitude towards the Wisterians after that. Some began to warm up to them by offering the use of their restrooms and gas-powered generators. Some even went so far as to let them enter the sanctity of their kitchens, although this was usually done sparingly as the Wisterians were never the tidiest of people. Deep-rooted animosities developed into acceptance, and even admiration for the hard work and innovation the Wisterians employed in nearly everything they did.

The greatest fruit of their labor, and arguably the most significant contribution to the integrity of the Stone House since its completion in 1882, was the digging of an artesian well on the property. It took a rag-tag team of young people—radicals, eco-militants, and hippies—to bring the gift of life-sustaining water to a house previously considered inhospitable. And they did it all without the “help” of town governance, RRP-certified contractors, or even necessary zoning permits. Their collective will to simply survive in their given environment made these typical checkbox items obsolete. In the end, it was their energy that prevailed.

That same summer, the Wisterians also re-shingled the roof of the Stone House and eradicated the Barn Owl problem that had been responsible for an incredible build-up of acidic excrement along the upstairs rafters. These actions were done purely in response to a century-old neglected living environment. When they noticed the roof was leaky, they were quick to fix it. When they realized the owls would pose more than just a health hazard, they removed them.

When they needed water, they tapped it from the ground itself.

It is important to realize that the Wisterians in this story are, ostensibly, “squatters”, which in its contemporary context is a derogatory term. The Wisterians had no legal claim to the Stone House, nor did they have any sort of jurisprudence to remediate its condemnable conditions. Nor did they have the ethical responsibility as homeowners to fix things when they saw something was wrong, even though they did anyway.

However, the difference between the vast majority of displaced peoples who commit to self-help in order to remediate their dwellings and those who resort to simply “squatting” is the difference between, as English anarchist Colin Ward described, “people who initiate things and act for themselves, and the people to whom things just happen.” Ward further details the difference between, "the state of mind that induces free independent action, and that of dependence and inertia."

I can not help but reflect longingly at the Wisterians, looking back in awe at everything they were able to accomplish that summer. The ability to eke out a do-it-yourself existence in today’s housing market is admirable not only for its brazen defiance of age-old imperialist land practices, but in its reclamation of one of the most fundamental and basic conditions of the human experience: to build and shape one’s own dwelling.

Should we stand and watch as these crumbling houses of our past are torn down and transformed into sea-view condos by power-hungry developers that only Sunset Key millionaires can afford? In a nation crippled by an exponentially worsening housing crisis, should we continue to push land speculation to its financial limit by building back bigger and better and more expensive? Or should we place incentives on restoring and repurposing the forgotten relics of our time, giving the hammer and the saw to the people who are already actively making positive improvements on their built environment?

The greatest lie the market economy ever told is that man is incapable of housing himself.