Black Legend: Myth of the Spanish Inquisition

What you're not told about the Spanish Inquisition.

One of the most bizarre events in the collective mass hysteria, which engulfed America in the summer of 2020, took place in a pleasant public park outside the California state Capitol. As has become commonplace in American political culture, a large crowd of infantile, functionally illiterate political agitators assembled to vandalize a historic monument with the tacit approval of local and federal law enforcement. If that were all there was to the story, it no doubt would have gone unnoticed, drowned out by the wider symphony of narcissistic political violence employed by the most enthusiastic supporters of the Democrat Party. But this monument was not the usual target of our friends and self-styled moral superiors on the new left like Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, or the inaugural black regiment of the Union army.

This statute was of the greatest Spaniard to walk the land that would become America, a tireless promoter of the temporal and spiritual interests of California’s native tribes, one of the two men chosen by the overwhelmingly liberal state legislature to represent the Golden State in the national Capitol, and a canonized saint of the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church: Father Junípero Serra. An 18th-century Franciscan professor of philosophy in Spain, Serra abandoned the security, honor, and comfort of his life in Europe to journey to the farthest reaches of the world to spread the Christian faith, without which it is impossible to please God, and the Catholic Church, outside of which it is impossible to be saved.

In doing so he became the founder of a string of Catholic missions in the land of Alta California; the cities of California bear the legacy of this glorious Catholic past in their names to this day: Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego, Sacramento, etc. These missions became not just centers of the Catholic faith and the arts of civilization, but like the Jesuit reductions in South America, bastions in which American Indians were protected from the predations of unscrupulous European explorers and Spanish government officials. In these reductions, a new entire society emerged where neophytes freely choose to center their economic, social, and political life around the liturgical mysteries of Tridentine Spanish Catholicism celebrated in dozens of mission churches, whose ruins are the most magnificent structures in the American Southwest, free from the conscription and abuse of Spanish rancheros and military garrisons. Undoubtedly, natives suffered from disease and the wicked actions of individual Spaniards, but in this story, the barefooted mendicant Serra and the Catholic mission stand consistently on the side of native rights.

Modern attempts to portray the California missions as the moral equivalents of Dachau are as dishonest as they are sinister. The truth of the California missions is told by archaeologist Dr. Robert L. Hoover:

Joining a mission community freely and for whatever reason, the neophytes were protected from the labor demands of the military and civilian settlers. In exchange, they were expected to stay and contribute to the support of their own community. Mission production was communal property, and most of it was redistributed back into the mission community. When work was not required, neophytes were allowed to travel back to their home villages or hunt and gather in traditional ways. Labor requirements were reasonable, spread over a large number of people, and conducted according to a flexible schedule. Mission neophytes were not starved. Historical records and archaeological evidence of thousands of butchered and cooked animal bones indicate that three balanced meals were provided each day, there was plenty of protein, and native foods continued to be eaten as snacks.

This archeological truth is borne out by historical fact, under the entire mission period of 1769 to 1834, the native population of California declined from 300,000 to 250,000. Yet, under the independent Mexican government which secularized the missions established by Serra, the population fell far more precipitously in a much shorter period: from a population of 250,000 to 150,000 in 1848, until finally under American rule the native population declined from 150,000 to 30,000 in 1870.

Amid dozens of deadly and untreatable diseases, the barefooted Serra walked from mission to mission, all the way from California to Mexico City to petition the Spanish government on behalf of the natives and advance the gospel in Spanish Mexico. The independent Mexican government and the ranchers who purchased the missions had far less concern for the welfare of California’s natives, whom they treated as property.

In every historical period the natives suffered from the same diseases and the lack of modern medicine, but in only one did they labor under the facades of Spanish mission churches: the period in which the least demographic decline took place. Clearly one must say, at the very least, that villainizing Fr. Serra as the face of all the abuses committed against the natives of California is an egregious instance of historical scapegoating. At most, one can say it is an example of the guilty parties directing blame at a saintly man building a new Christendom, swept away too soon by the ocean of blood pouring out of the anti-Christian revolutions in Paris and Madrid.

The libel of Junípero Serra will have no effect on his eternal happiness in heaven, but it does have an immediate and obvious effect on all of us who still live here in the land he labored. Serra is not attacked in isolation or even primarily as an individual, but as the embodiment of Christian and European culture on the North American continent. Insofar as this is the case, the legacy of Serra and the larger Spanish civilizational project in the America he embodies is not just the concern of the Republican Club’s resident Catholic Campus Conservative, but all people of goodwill interested in truth and the preservation of all that is good in American and western history. All Americans must be as ready and able to give a defense of Serra as his contemporaries, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, whose success in the revolution he prayed for.

The ahistorical attack on Serra is just one star in the larger constellation of the historical attack on Spain collectively referred to as ‘The Black Legend’. According to this narrative, Catholic Spain is portrayed as a uniquely backward, intolerant, and barbarous country, contrasted with the liberalism and benevolence of the northern Protestant counties. The ultimate embodiment of this legend is the Spanish Inquisition, no crime is too horrible to be attributed to this tribunal, no alleged atrocity is too outrageous to raise suspicion of its credibility.

The only problem with this entire narrative, like the specific instance of the libel of Serra, is that it is simply untrue and believed to be untrue by modern, mainstream, historiography. In the words of the BBC, “Four centuries of condemnation have made the Spanish Inquisition a byword for cruelty, terror, and tyranny. But this image is false.”

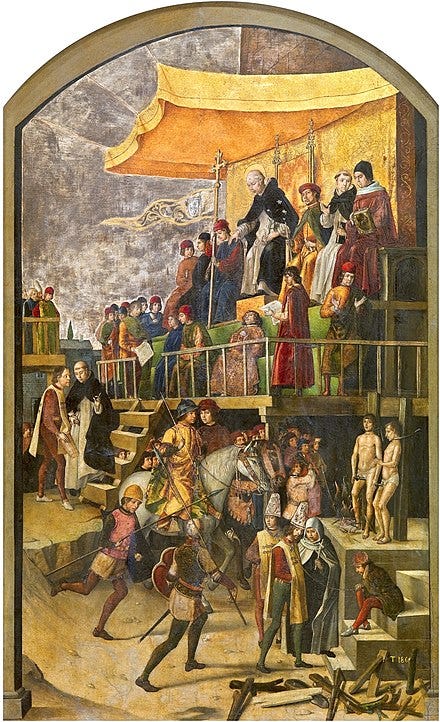

According to those issuing the accusations, anywhere from hundreds of thousands to millions of pagans, Protestants and Jews were hunted down and executed by the Inquisition in the course of its nearly 400-year history from 1478 to 1834, in courts akin to the show trials of the Gestapo or KGB. The lurid stories of Protestant polemicists of the 16th century, who had never been to Spain, blossomed into the fantastical anticlericalism of Voltaire, to whom the Inquisition was “that bloody tribunal, that dreadful memorial to monkish power,” which in turn animated the philistinism of modern professional agitators.

Like so much of Voltaire, this colorful description is divorced from reality. Historian Henry Kamen explains:

By the 1560s, indeed, Spain was one of the countries with the lowest level of executions for religious reasons. … The proportionately small number of executions is an effective argument against the legend of a bloodthirsty tribunal. … it would seem that during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries fewer than three people a year were executed by the Inquisition in the whole of the Spanish monarchy from Sicily to Peru, certainly a lower rate than in any provincial court of justice in Spain or anywhere else in Europe. A comparison, indeed, of Spanish secular courts with the Inquisition can only be in favor of the latter.

So far from the torture chambers of popular Monty Python imagination, the prisons of Inquisition courts were superior to secular courts, where Kamen documented multiple instances of prisoners in secular courts blaspheming to be transferred to Inquisition prisons:

There is the case of a friar in Valladolid in 1629 who made some heretical statements simply in order to be transferred from the prison he was in to that of the Inquisition. On another occasion, in 1675, a priest confined in the episcopal prison pretended to be a judaizer in order to be transferred to the inquisitorial prison. In 1624, when the inquisitors of Barcelona had more prisoners than available cells, they refused to send the extra prisoners to the city prison, where “there are over four hundred prisoners who are starving to death and every day they remove three or four dead.” No better evidence could be cited for the superiority of inquisitorial gaols than that of Córdoba in 1820, when the prison authorities complained about the miserable and unhealthy state of the city prison and asked that the municipality should transfer its prisoners to the prison of the Inquisition, which was ‘safe, clean, and spacious. At present it has twenty-six cells, rooms which can hold two hundred prisoners at a time, a completely separate room for women, and places for work.

The meticulous records of the Inquisition show us why one would readily put themself at the mercy of the Inquisition. According to Professor Stephen Haliczer of the University of Northern Illinois,

In fact, the Inquisition used torture very infrequently. In Valencia, for example, I found that in over 7000 cases I found that only two percent experienced any torture at all and usually for no more than 15 minutes and less than one percent experienced frequent torture… I found no one suffering torture more than twice.

Contrasted to English courts, where permanent maiming was the regular punishment for crimes against property, the Inquisition's record is positively enlightened. This is not the opinion of some right-wing Catholic blog on some corner of the internet, but a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and former professor of the Council for Scientific Research in Barcelona Henry Kamen. The evidence is overwhelming in the Inquisition's defense that the reliably left-wing English journal The Guardian could run a piece entitled ‘Historians say the Inquisition wasn’t that bad’

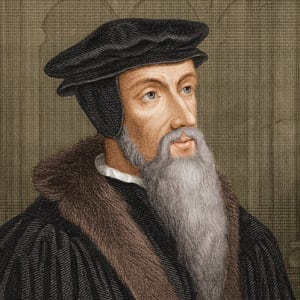

Not only was the Inquisition not that bad, but it was also a positive good that defended the most just, noble, and advanced society in the world. At a time when the champion of Protestantism, John Calvin, was operating a theocracy and murdering his personal enemies.

Calvin wrote in a letter:

Servetus lately wrote to me, and coupled with his letter a long volume of his delirious fancies, with the Thrasonic boast, that I should see something astonishing and unheard of. He offers to come hither, if it be agreeable to me. But I am unwilling to pledge my word for his safety, for if he shall come, I shall never permit him to depart alive, provided my authority be of any avail.

Elsewhere, the cruel tyrant Oliver Cromwell was waging a war of genocide against Catholic Ireland, which reduced Ireland’s population by as much as 41 percent.

In comparison, the Spanish Inquisition was both merciful and restrained in its judicial task. At a time when Protestant Europe and much of Catholic Germany were swept away by hysteria over-imagined cases of witchcraft, the Inquisition recognized that the “witch hunt was almost entirely based on lies and self-delusion,” following the Augustinian and Thomistic opinion that witches possessed no power to manipulate the physical elements.

At a time when France, England, and Germany were convulsed by religious war, Spain under the Inquisition maintained its religious and temporal harmony.

At a time when England and France suffered under absolutist royal tyranny, Spain under the Inquisition maintained the medieval order of limited monarchy and the great Spanish inheritors of the medieval scholastic tradition could expose the most radical embrace of true liberty of the age. Francisco Suarez, a Spanish Jesuit at the time of the Inquisition:

If a wrongful deed is prohibited by divine law, no law made by an inferior can annul the obligation imposed by the superior; consequently, [such an inferior] cannot impose an obligation, for his own part; and therefore, his law on the deed in question cannot be valid. It was to this justice of law, indeed, that St. Augustine referred, when he wrote “In my opinion, that is not law which is not just.”

Like the slander of Junípero Serra by states which horribly mistreated the natives of California, the Black Legend of Spain spread by the forerunners and champions of modernity, progress, and modern civilization is an example of guilty parties heaping the burden of their crimes on a guiltless party. The images of judicial horror and torture conjured up by the popular image of the Spanish Inquisition do not accurately describe what was, in reality, a modest and dull bureaucratic arm of the Spanish crown, but they do describe the revolutionary tribunals of the left-wing dictatorships which swept away the world of the Spanish Inquisition: The Committee of Public Safety of Revolutionary France, The Cheka of Bolshevist Russia, and The People’s Courts of the Third Reich, are exactly the institutions which portray the old Habsburg Empire of Spain and Austria as the embodiment of darkness, torture, and superstition.