The Myth of Objective Based Merit

Donald Trump's "merit-based" approach disregards socioeconomic status and multiple loopholes, and will do more harm than good.

Donald Trump’s administration believes that college admissions are rigged—and they’re right, but for the wrong reason. If they continue combating the wrong injustice, more harm than good will come from it. As part of the deal recently signed with Brown University and Columbia University, The Trump administration would gain access to admission and enrollment data—something that has not been seen by the public (which I believe plays a role in the plummeting confidence in higher education we see today, but that’s a discussion for another day). The administration claims that it only wants to promote “merit-based” opportunities in all facets of life, including college admissions.

The administration argues that elite colleges and universities are evaluating and admitting applicants based on race, which became illegal following the Supreme Court’s 6–2 ruling in 2023 in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. They claim that elite institutions are giving preferential treatment to minority students based on racial identity. However, the real injustice in college admissions lies in the divide between socioeconomic groups. Rich students—regardless of race—are significantly more likely to enroll in elite, highly selective institutions than applicants from similar racial backgrounds but with lower income. Moreover, students from the top 1% of the wealth distribution are twice as likely to attend an elite college or university—even with similar SAT scores.

This divide between the wealthy and everyone else will only worsen under the administration’s narrow view of “merit.” In their eyes, “merit” is reduced to a few quantitative metrics that are egregiously skewed in favor of wealthy students. Metrics they support to “demonstrate merit” include standardized tests (SAT, ACT, AP scores) and grade point average (GPA). If elite universities are coerced into relying solely on these metrics, the socioeconomic diversity of their student bodies will quickly erode within just a few admission cycles. Subsequently, racial diversity will likely decline as well, due to the demonstrated connection between race and income.

I also predict an increase in GPA inflation, a phenomenon known as “gradeflation” in which the average GPA has sharply risen over time, despite the average student’s IQ or knowledge remaining stagnant (contradicting the Flynn Effect). If the Trump administration forces highly selective colleges to place more emphasis on GPA and test scores, students may begin to “sandbag” classes to maintain high GPAs. To “sandbag” classes, a student intentionally selects classes in which he or she knows that they will get an A or B for minimal amount of effort. Grade inflation at the high school level will likely skyrocket, and teachers will feel pressured to award higher grades as students will need to rely more heavily on their report cards to gain acceptance into elite institutions.

However, there are ways colleges can prevent a gradeflation catastrophe if this becomes the standard in the admissions process. One way is by placing greater emphasis on academic rigor—such as taking Advanced Placement (AP) or International Baccalaureate (IB) courses—which can justify a slightly lower GPA when recalculating applicant grades. Another approach is for colleges to be more transparent with applicants, assuring them that it's okay to earn a C in history if they are excelling in STEM courses and intend to major in a STEM field. Students should not be discouraged from challenging themselves academically for fear of damaging their GPA and jeopardizing their chances at elite schools.

Another major issue with relying heavily on standardized test scores and GPAs is that a plethora of evidence shows these metrics are severely skewed toward wealthy applicants. There are clear disparities in scores across racial groups—White, Asian, Hispanic, and Black students—largely due to socioeconomic factors that students have no control over. The chart below illustrates the score distribution by income level from a 2017 New York Times article:

Students from the top 0.1% of income earners had nearly 4 in 10 scoring at least 1300 on the SAT. In contrast, only 2.4% of low-income students—mostly Pell Grant–eligible—reached that score. This shows that if elite colleges place greater emphasis on standardized testing, we will see increased enrollment of wealthy students, who are more likely to achieve the scores elite schools seek.

Lastly, if the administration truly cared about “merit,” it would focus on closing the actual loopholes in the college admissions process. The three biggest loopholes include legacy/donor admissions, recruited athletes, and the “transfer method.”

Legacy/donor admissions involve colleges favoring applicants with family ties to the institution—whether their parents attended, donated significantly, or are influential employees (like department chairs). Legacy admissions have been heavily criticized in recent years, prompting some elite institutions like Amherst College to eliminate the practice.

Recruited athletes also have a nearly guaranteed path into selective colleges. While this has long been acknowledged, it came under public scrutiny thanks to Rick Singer and the Operation Varsity Blues scandal, where coaches helped fabricate athletic credentials to secure admission. A recent study found that recruited athletes are among the most successful applicants at elite institutions.

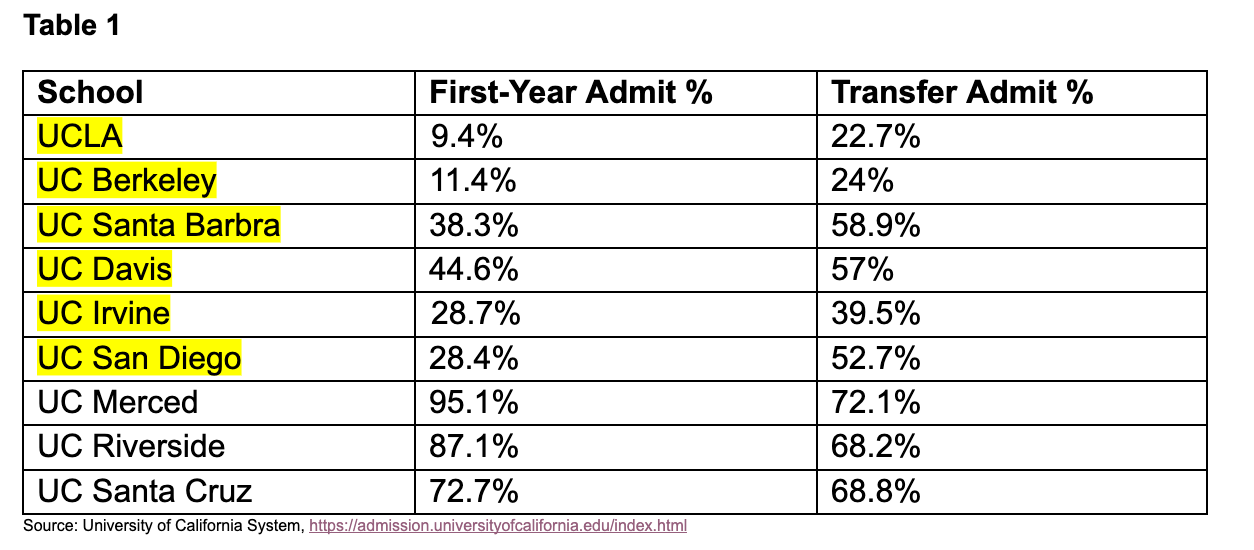

The transfer method is less common but still notable. It involves gaining admission by transferring from another college—often a community college—rather than applying directly as a first-year student.

The data above shows that the two highly selective UC schools –UCLA and Berkeley– have significantly higher acceptance rates for transfer students. This trend is continued with moderately selective UC schools (UCSB, Davis, Irvine, and UCSD) in which the First-Year Admit rate is significantly lower than the Transfer Admit rate. Additionally, there are fewer total transfer applicants, meaning admissions officers can dedicate more time to each file.

I’m not suggesting that all transfer students use this route maliciously, but the numbers indicate that it is notably easier to gain admission through transfer—sometimes by double-digit percentage points—than through direct first-year application. Applicants in the “know” (ie. applicants with access to high quality college counselors that are typically expensive and reserved for wealthy clients) can utilize this method as a side-door in the admissions process to a moderately or highly selective UC school. Interestingly, less selective UC schools admit a higher percentage of applicants in the first-year cycle than in the transfer cycle.

If the Trump administration successfully forces highly selective colleges and universities to adopt its stance on “merit-based” admissions, the consequences will be disastrous—especially for low-income students, regardless of race. With rising grade inflation and continued reliance on metrics skewed toward wealth, we’ll likely see even more affluent students dominating elite admissions, preserving the status quo and further stifling the upward mobility of low-income talent. In turn, higher education will continue to see plummeting public confidence and the reputations of these schools will continue to be tarnished.

A well-written piece. I don’t agree with all the points, but I’m glad you wrote and published it. A healthy and varied discourse is good for all of us.

Agree with most of this, but it would be interesting to see the data on which high schools offer more AP classes. It may be that the wealthier towns do, which would then make that point moot. More challenging would be the honors classes which rely more on actual all around intelligence, vs the memorization that goes along with AP studies. Class placement/academic class division (honors, regular, remedial) is an issue itself along the lines of grade inflation but that’s another story. Thanks for writing this piece.